SparkFun was started with the goal to make it quick and easy for anyone to invent and prototype. Part of that goal depends on our ability to make and revise products continually to stay relevant to what the DIY electronics community is interested in, from the latest trends - like IoT and drones - to classic programming and electrical engineering. SparkFun has been consistently good at in-house production of simple, functional specialty boards and kits designed to give prototypers shortcuts; today, almost half our sales (44%) come from making and selling “SparkFun Originals.”

To coincide with Manufacturing Day 2014 (this year on Friday, October 3), I walked around the building to see if I could document how we put a dozen or so new products on the website every week. Many things contribute to that process, from Lunch & Learns to the early adoption of the beer license, but the engineering department unquestionably leads the charge.

“What SparkFun engineers do at work is what we would choose to do if we didn’t have jobs,” said engineer Mike Hord. “But we would definitely abandon more things and operate with less structure.”

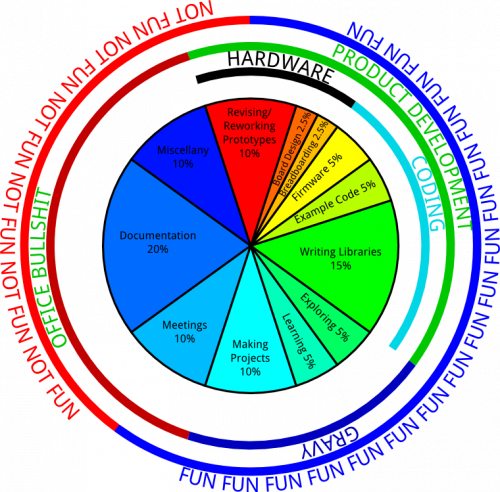

Here’s Mike’s depiction of how SparkFun engineers spend their time:

There are 13 people (seven of which are engineers) in the Engineering Department. Each engineer typically works on five or six projects at a time, and completes around a dozen new products each year.

A significant part of the engineering process is the weekly engineering meeting. Two hours every Monday morning are dedicated to pitching and evaluating new ideas. There is a lot of laughter heard through the walls, but there is at least a hint of seriousness to the meetings, since the group is vetting what will eventually be made by SparkFun.

SparkFun’s engineers spawning new ideas

DISCOVERY

Ideas are born everywhere - inside and outside our headquarters. Fifteen percent of the ideas for SparkFun Originals come from outside the building (which we then pay royalties on). But within the building, there is one staffer dedicated to fueling the new product pipeline.

“My job is pretty cool,” said Technical Researcher Pearce Melcher, “Because I get to have to learn about new technology and I get my hands on things before they are released. What I bring to the table is a small amount of expertise in a lot of areas. I am a hobbyist with a mechanical engineering background. Before I was an employee, I was a customer.”

One engineer’s input holds a bit more weight on the final cuts - Chris Taylor, Engineering’s project manager:

“We take a lot into consideration when deciding which ideas to pursue; originality, value-add, costs, popularity, novelty, timeliness, a standard found in many projects? Is it cool? Will it make money? Is there an engineer with expertise in that area? And sometimes we just pull rank.”

And some products come straight out of someone’s hobby, such as the SparkPunk.

Byron Jacquot, an engineer with an interest in music technology said,“The first electronics book that a lot of engineers had was the Forrest Mims book originally sold in RadioShack which introduced the AtariPunk design. Lots of companies manufacture an AtariPunk kit. I wanted to put a spin on it - make it hack-able and make it sound better.”

If you are a music tech aficionado, this is your kit.

Ideas that pass muster are put into our open source bug tracking software, which doubles as a project management tool. An engineer is assigned, if there isn’t one already, and priority is discussed - products that don’t already exist elsewhere are given precedence.

PROTOTYPING

After the discovery process, the engineers start prototyping. This is iterative and requires real paper and pencil and, well, engineering -revising reworking, board design, breadboarding, firmware, etc. Eventually a “green board” or prototype board is conceived (final boards are SparkFun red).

“At least one change is always made to green boards – some major, some minor,” said Byron, who ran into trouble when a vendor messed up and delivered a PCB without any drill holes for a number of components.

After a prototype is revised, it will be tested and then breadboarded. This requires a 3rd party - SparkFun uses OSHPark or Gold Phoenix for PCB assembly. The engineer then tweaks the schematic, creates a working circuit, finds the parts and creates a Bill of Materials.

“Arriving at a stable board is tedious,” said Byron, “because if you get it right, you cause less agony for others.”

Manufactured prototype boards then make another appearance at the Engineering meeting for review. Every Monday morning, there are two or three boards under review.

“At this stage, a decision is made whether to go to a full run or not,” said Chris.

This is usually where Yak Shaving comes in.

Mike Hord’s definition: “It's when you need to learn a new tool to produce the necessary documentation, and in order to run that tool, you need a specific version of Python, and in order to download that version of Python, you need to update Chrome, and in order to update Chrome, you need to fix your internet connection, and in order to fix your internet connection."

The eventual result is open-sourced Eagle files, schematics, PCB files, design documents, hook up guides or kit cards, example code, libraries and GitHub repos.

"We view GitHub pages up on the screen during the Engineering meeting," _said Toni, SparkFun’s GitHub guru, _"and we actively file issues and keep records."

The importance of this tool cannot be overstated.

"Our most popular Github repository, the SparkFun Eagle Libraries, averages more than 200 views per day, and has contributions from over a dozen SparkFun members and many community users."

“This is the kind of information that was helpful to me when I was a student (in Applied Math at CU Boulder),” _said Toni, _“so I Iike sharing it now. I also get to know what is going on with all of our products.”

We also test everything at SparkFun. Or at least we try.

“Kits like SparkPunk are bags of parts, so testing is done by having other people build them. We also do beta testing in the lab, and then we make fixes,” said Byron.

Board assemblies, on the other hand, get a custom designed test jig. Pogo pins (aka bed-of-nails) are used – boards are pressed down on a jig designed to test all the solder joints. The jigs are designed to turn everything on, and a green LED lights up if all is well. If not, the techs fix errors manually. For more on this, see Constant Innovation in QC.

“Revisions are done at this stage even if it means the engineer has to jump all the way back to the design of the board,” said Test Engineer Pete Lewis.

“What I like about my job,” said Lewis, “Is that I can be creative. We ‘keep it scrappy’ and customize specifically for what we need. I am a self-taught engineer and I have designed a couple of products for SparkFun (Binary Blaster and Simon Tilt). All of us in QC came from production.”

PRODUCTION

Parts are purchased for final boards, which are then built downstairs by hand in Production.

Figuring out how many boards to build for the initial run requires basic math. A buck panel is a unit of measure by Gold Phoenix that is $100 of square inches of circuit boards. We purchase 1, 2, or 3 buck panels. Once this is done, Inventory orders the panels and parts, and part numbers are put into the system.

After testing, a full run is scheduled and additional parts are purchased. This information feeds the schedule in production.

“Coming up with the debut quantity,” said Director of Inventory Jordan Hanie, “Is a digital blind spot and requires a manual, difficult process and cooperating with others. Our goal is to not go live with insufficient quantity or missing supporting material. I usually pick a mid-range guess that fits with a benchmark product.”

KITTING

At any give time, about 33 percent of SparkFun Originals are kits like the SparkPunk. What does it take to be a good kitter?

“Some good headphones and good taste in music.”

“You have to have a good sense of humor.”

“Dexterity and patience.”

Says their manager, Richie Maestas, “This group is hardworking and brilliant.”

“It is a bit like a knitting circle.”

Each kitter works on 25-30 batches of kits over the span of a week, usually resulting in 4000 total kits per month.

“One of the biggest challenges is that there are so many different kits. Period. But at the same time, we love new kits,” said kitter Jordan Valdez.

On average it takes us 1.3 minutes to put together one kit. Some take 20 seconds and some take six to seven minutes. All of the kitters have side projects, and they all work on automating and optimizing the efficiency of their jobs. A lot of kitters end up advancing through the ranks at SparkFun; the group is open and communication is key.

CFO Richard Parker said, “Kitting is the only place in the building where I can really be myself.”

LAUNCH

“SparkFun design and programming code is open source, and we have always used the Beer License,” said CEO Nate Seidle, which says essentially, “feel free to use our code and then when we meet in person down the road, buy me a beer.”

At this stage, engineering has left the product design spotlight. Engineers continue to receive email updates on every comment posted to one of their boards, and the keep an eye out for pitfalls customers are having and things they like. It is through this interaction with the community that the designs are improved.

“Writing the Hook Up Guides – especially for kits – is nontrivial,” said Byron.

The engineers also pass their hookup guides on to Jim or Joel for editing. Fritzing boards (visual renderings of how the board is hooked up) are created by Pamela Cortez to accompany the hook-up guides. This file also goes into GitHub.

The product is given a SKU, a description is written by Chris McCarty in Catalog, and a product page is built and given all the documentation links. Juan and Chelsea shoot and edit product photos, and Nick Poole, Robert Cowan, and Gregg Barclay prep for and shoot the New Product Friday video.

SparkFun’s product photos have been one of the SparkFun mainstays from the early days.

“After the product is released, we anxiously watch for, respond to, and are amused by what people say in the comments,” said Jordan Hanie.

Knitting circle... looks more like "The Last Supper."

Good eye.

But there's only 8 people at the table and no one is reaching for a dual, in-line package.

Yeah, regarding office bullshit, I wouldn't necessarily put documentation in that category. For me, office bullshit consists of things like filling out expense reports, mid-year reviews, reorganizations, and the like. Documentation is your friend! Well, sometimes.

One of the approaches to the daily grind that has been gaining traction where I work is the elimination (as much as possible) of multitasking. Focusing on finishing tasks, as opposed to starting them. Setting clear priorities across departments, because there can really only be one most important project at a time. Trying to limit interrupting your coworkers, while at the same time, having the cojones to tell people no. Remembering that being responsive to someone's email request doesn't automatically mean dropping everything right now to send a response. Are you able to get things done? What about when it comes time to just kill the engineer and move out of development and into testing?

I'm curious how you guys handle projects with specific requirements. Not all new products are the direct result of a single innovative idea. Many times, there are requirements (user, interface, safety, legal, etc.) that need to be incorporated into a product's design. How do you determine if you made what you were supposed to make, and if it's what the customer actually wanted/needed?

+1 on not including documentation in that category. Documentation is the most important part of any product. I will not buy a product that I cannot understand. When I go to actually buy a product, the decision is based on the documentation. Does it exist, is it intelligible, does it tell me what I need to know to get the product working in my environment, etc.

Quality of documentation is more important than quantity, too. An effective engineer can generate a 1-page document that is more informative than an ineffective engineer's 400-page document.

Being able to produce good documentation indicates good organization, the ability to communicate with others and a complete understanding of the product. Bad documentation is an indication that a company is poorly managed, does not care about their customers and hires ineffective people.

Since documentation is the basis for affordable manufacturing, defect control, customer support, advertising copy and so much more, I'd be having an attitude adjustment session with any of my employees who put it into the office bullshit category.

Yes, documentation is critically important to SparkFun - exceptional documentation in particular - and is one of the reasons we are on the map. But my take on having an attitude (or a sense of humor) about aspects of our jobs that can be drudgery is different. Documentation is a necessary and a good engineer knows that and has the discipline to spend a fifth of their time on it, but if they personally do not find it fun, I am okay with that. And if they cope with it by having a sense of humor about it, all the better. Success requires discipline. But disciplined work does not necessarily have to be enjoyed.

Wow, you mean you guys are using the same old analog model TEK 'scope that I am ('453-4)? I guess these old warhorses never die!

Sparkfun product pictures are always fun to look at. Can Juan tell us whats the setting he keep while taking these high resolution pictures.

It's constantly changing. I am always trying to improve image quality. Lately it's f/25, 1/200s, ISO 100 with a 60mm lens.

FUN FUN FUN FUN, NOT FUN NOT FUN NOT FUN. I love it.

"OFFICE BULLS--T??? I'm not too stingy about it, but considering how Sparkfun has always maintained a very 'family friendly' image, it seems like a weird thing to post of the front page. Other than that, great post!

I know it's going to come as a shock to some, but actually we do some swears.

Well, maybe a lot of swears.

Technically, "shit" is a vulgarity, not an obscenity or swearing. In the Judeo-Christian cultures, the prohibition against swearing comes from the Decalogue where taking God's name in vain is prohibited. Since God's name has nothing to do with excrement, in theory it'd be OK to use the vulgar form in even in church, at least as far as blasphemy and swearing go. Of course, you may get thrown out for being vulgar, but it's not swearing.

Thanks for the comment (and the compliment). A couple of people on this end also questioned whether to leave the expletive in Mike's graphic. I said, "I will take the heat." The fact that you made a comment implies that there were probably others that were taken aback as well, so I wouldn't do it again. I kept it in because I found it more authentic. The fact that I have a teenager and given the language in popular culture these days - I guess I have become a bit numb.

meh, I don't think the FCC cares about shit anymore. pun intended.

Wait, so SFUptownMaker is Mike Hord and Byron Jacquot? Both names link to that profile...

Oops - that was my bad, I made the fix. Thank you!

One thing I've noticed in the post is that there are no deadlines.

Can anyone explain how having no deadlines (or soft deadlines) help/hurt the manufacturing process with creating new products? Updating old ones with newer revisions (due to a trace mistake, or something else).

In engineering we don't have a hard, fast rule about deadlines. Sometimes we have them, other times, not so much.

If there's a real mistake in something- a solid, no foolin', this-product-is-unusable flaw- we pull it from sale and fix it. The priority of the fix has to do with how popular the item is: obviously, I'm not going to bump, say, Edison board development in favor of something that only sells 10 units a week.

Deadlines on new products are a little more flexible, but again, always stack up against other products. Sadly, this does occasionally lead to products that languish, but in general, we're pretty good at turning up the priority to prevent things from aging forever.

Great observation. We do have deadlines - especially for the core aspects of our jobs - perhaps not so much for our side projects. For example, I have to get a report out on the same day at roughly the same time each week. In fact a lot of the "launch work" is on a weekly deadline basis. I know Engineering has and discusses deadlines, too, as does Inventory, but theirs are much more complex. Thanks!