Quite often, when I get an idea for a potential project, especially one that consists of a number of functions, I, like many of you, like to start with a smaller proof of concept project. Taking smaller steps to make sure that each component of the project is even possible can save time, money, and frustration. And so it was with a project idea I recently had. I want to build a submarine. I don’t mean that I want to build a full-sized one that I can hop into and explore the depths of the sea, (wait, of course I want to do that, but let’s be practical,) but a smaller, autonomous underwater rover that can do things like guide itself to specific points in a body of water, take depth measurements, water temperature readings, perhaps shoot some video, and who knows what else!

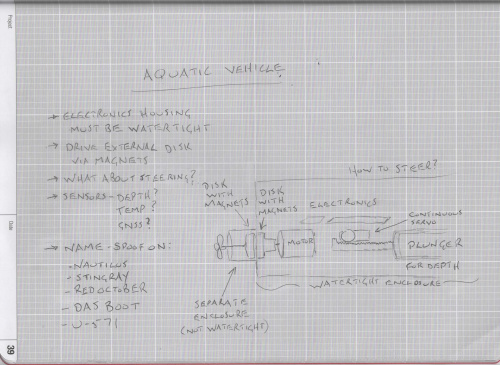

I don't always do sketches of my projects, but sometimes the notes and visualization help.

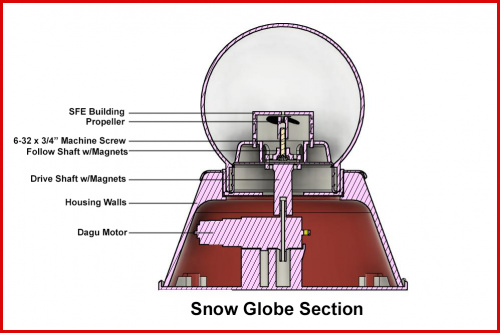

I figure the first thing I need, the thing that separates an autonomous rover from a piece of driftwood, is a means of propulsion. A motor and a propeller, right? Of course, we all know that water and electronics don’t play well together, so what method could I use to make sure that water can’t reach the motor? While I honestly have no idea if it’s possible, plausible, or even in any way remotely smart, I thought that perhaps I could have a driveshaft from the motor that held a series of neodymium magnets, with the end placed against the wall of the enclosure. Outside of the watertight enclosure would be a second shaft, with its own set of magnets, attached to the propeller. I mean, the theory of it is sound enough, right?

So I knew that I needed to prove, if only to myself, that this was possible. But I also wanted to have some fun doing it. I decided that a good way to try to prove that a propeller could be spun without physical contact to the motor itself would be to make a snow globe that required no shaking, no touching. Just wave a hand in front of it, and excite the snow within. The motor and electronics would be hidden in the base, and the propeller, inside the globe, would excite the water and snow. Even with your hands full of gingerbread men and egg nog, you could still enjoy the magic of the snow globe! Since the circuit itself was really quite simple - just a microcontroller, motor driver, and proximity sensor - the now not-so-simple proof of concept project would allow me to do a little bit of 3D design and printing.

The size and placement of the motor dictated the size of the base.

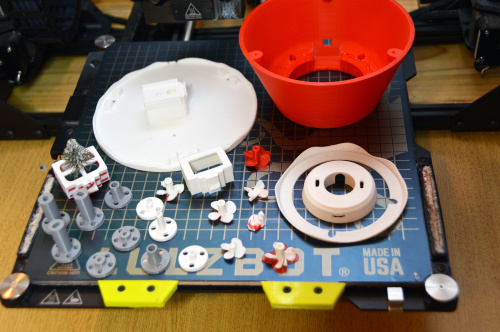

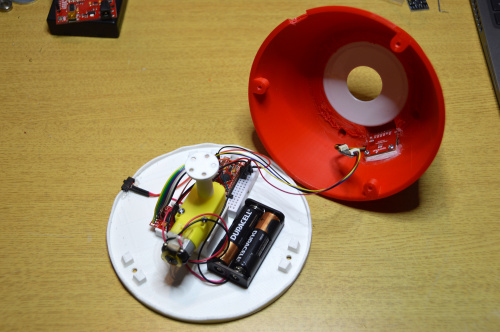

For the globe itself, I went to the Dollar Store, and found DIY snow globes there. Maybe not the best, but they look pretty good, and the price was right! I had some small disk magnets on hand, so I designed the shafts around those. For the motor, I had planned on using a basic hobby motor, but I couldn’t spin it slow enough for my test. I instead went with one of our Dagu Hobby Gearmotors. This increased the size of the base, but not too terribly. I had also planned on running the circuit off of 4 AA batteries using a cube-shaped battery holder, but since we’ve retired those, I decided to go with just 3V. I used one of our 3.3V - 8MHz Pro Micro boards to facilitate this, plus a dual motor driver and our Qwiic proximity Sensor, and I had everything I needed.

A number of revisions, a few failed prints, but I finally got everything printed.

A place for everything, and everything in its place.

Once the code was written, the parts printed, and the components put into place, I did my first test run. I powered up, ran my hand in front of the base, and the motor spun for the requested five seconds. Great! Next, I slid the lid of the globe into the base, then placed the insert with the 3D printed “ground” and the propeller down onto it. Once again, a wave of the hand past the proximity sensor, and what do you know, the propeller spins!

At this point, the propeller spun quite well. Concept proven!

Time to go for it all. I filled the globe with distilled water, plus a little but of glycerin to thicken it up, which makes the snow fall more slowly, dumped in the snowflake glitter, and with hot glue gun in hand, sealed the entire thing up. No going back now. I slid the now hermetically sealed globe down into the base, powered it up, waved my hand in front of the sensor, and… nothing. Well, not exactly nothing. The propeller moved and shook a little, but it didn’t spin. Well, at least it looks pretty.

"An escalator can never break: it can only become stairs." ~Mitch Hedberg. Similar truth for an automatic snow globe.

However, I’m not at all discouraged by this. Before I submerged the propeller in water, I was in fact able to get it to spin. Have I added too much glycerin, making the mixture a little too thick? Perhaps the propeller is hitting the inside of the building in which it’s housed. I think that the most likely explanation is that my magnets simply aren't strong enough, or are too far apart. Whatever the reason, I still feel confident in moving forward with this project. I will post updates as I continue with the build, but it will probably be a while before everything is up and running. As I type this, the current temperature here in beautiful Colorado is -13°F, and I have absolutely no desire to be anywhere near water. So until my next update, from all of us here at SparkFun, Happy Holidays, and Happy Hacking!

If you making a DIY snow globe, you might as well make it unique, right? SparkFun HQ in all it's snowy glory!

As a retired (recovering?) Engineer, my first thoughts on reading this is "of course, it's feasable -- lots of historic presedents: for feasability of keeping electrical/electronics dry, try World War One submarines, and for the idea of magnetic coupling, try the gadgets chemists use to stir stuff with a magnet in the bottom of a beaker".

I'll also say this about the idea of POC -- it's always a very good idea to take things in small steps. For instance, when writing complex code (i.e., more than about 5 lines!) write a few lines at a time, then test it, and then fix what you've added until it works before adding more. It is FAR easier to find bugs in the small new section, than to plunge in and find why a tens-of-thousands line program crashes! (Guess how I know! :-)

I agree wholeheartedly, especially when it comes to code writing! I've seen so many beginners write a couple hundred lines of code to do half a dozen things, only to stare blankly at their project when it doesn't work. Small sections, and comment your code! (File this under "Things I would tell my younger self".)