For most of the year, Selden (pop. 216) is a quiet farming community deep within the vast fields of Kansas. But every July 4th, a team of highly-skilled amateur pyrotechnicians from around the country travel to this small town to put on a fireworks show worthy of professionals.

The ringleaders are contractor Joe Keating, and aerospace engineers Lee Jasper and Kyle Kemble. They meet in Selden because Joe has deep family roots there (they run the operation out of his grandmother's house). Each year they're joined by about a dozen family members, friends and acquaintances, all hand-picked as if they were in a caper movie. The resulting team has been doing this for quite a while; this year will be their 12th annual show.

-> Kyle Kemble, Joe Keating, and Lee Jasper <-

The team does this mostly for the fun of it. Fireworks are illegal in most of their home states (for good reason), and as Kyle puts it, putting on this show lets them scratch a pyrotechnic itch they normally wouldn't be able to. But they also do it in service to the people of Selden and the surrounding communities – the show they put on is entirely self-funded.

The planning for each year's show begins the day after the previous one. While the team is recovering in the shade outside Joe's family home, they talk about what went well, what didn't, what new equipment they could build, and potential themes and music. The team then disperses to their home states and starts working on next year's show.

Every April, Joe, Lee and Kyle attend a convention put on by their fireworks manufacturer, Red Rhino. The company demonstrates new products (live in their own show), and announces which products they'll be retiring (often with deep discounts). These are consumer fireworks, not the highly-regulated shells that highly-regulated professionals use. However, the products the team choose for the show are still extremely powerful, and they set off thousands of pounds of them. This year they purchased nearly 6,000 pounds of fireworks, half of which they'll use in the show, the rest they'll sell to finance the enterprise, along with donations from the team and members of the community.

During the spring the team also works on their firing system, which gets more sophisticated every year. They've come a long way from the first shows, which used the old-fashioned method of people running around with lighters.

Joe built their first electrical firing system in 2013 while he was out of work with a shoulder injury. It consisted of 18 household light switches connected to alligator clips, all plugged into an AC extension cord (kids don't try this at home!). Slightly alarmed by this, Lee and Kyle built an Arduino-based system the following year. This consisted of two Pelican cases, each containing a WiFi-capable Arduino Yun, 48 SPI-controlled relays, lead-acid batteries and a key-based arming system, all built to NASA specs. More or less.

The advantage of an electronic firing system is the precise timing it allows, not to mention that it separates people from the immediate vicinity of explosives, which is never a bad idea. Instead of a fuse that gives you 10 seconds or so to get away, electrical ignition occurs almost instantly, making complex and precise, computer-controlled choreography possible.

But as we all know, bugs aren't just possible, they're inevitable. For the 2014 show, the original plan was to wirelessly connect a laptop to the two Arduino-based boxes (password-secured, of course). However, WiFi connectivity was found to be iffy during testing, so the decision was made to hardwire the system using ethernet cables instead. Even then, one of the boxes became unresponsive in the final minutes before the show. Kyle cautiously entered the field to reboot it manually, only to have to turn and run as the box immediately set off all 48 of its fireworks...

Thanks to the team's commitment to safety, Kyle was fine (in fact, the team has never had a serious injury). The crowd loved the "finale" occurring at the beginning of the show, and a picture of Kyle silhouetted against the conflagration became part of the team's official logo. But the team learned a valuable lesson about testing. That particular bug was found and squashed, and the boxes served the team well in subsequent years.

A few days before the show, the bulk of the team arrives in Selden. Following the master spreadsheet, they proceed to unpack the fireworks, secure them to wooden pallets, and install the firing components (called "electric matches") in place of the original fuses. This is delicate and potentially dangerous work, but the team has researched how to do this safely. Don't try this yourself without doing the same.

Show day starts before sunrise, to try to finish laying out the field before the midday heat. The early shift hauls the pallets to the town baseball field, and places them in their predetermined positions. The late shift then moves in to wire the hundreds of electric matches into the firing systems.

In past years, this took thousands of feet of two-conductor wire, strung out like a spiderweb across the field (and just as likely to ensnare careless footsteps). But the firing system continued to evolve, and starting last year each pallet now contains its very own mini-controller.

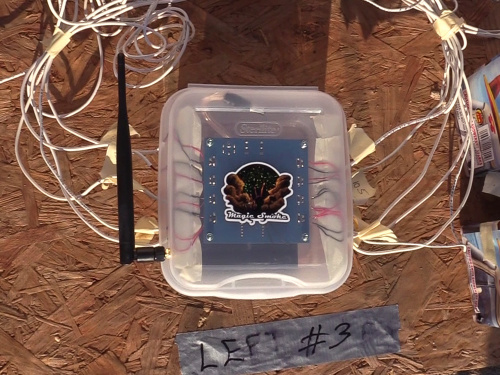

The new system, dubbed "Magic Smoke" and designed by team members Mike Mozingo and Brian Roth, consists of a custom PCB with a microcontroller, WiFi and eight high-current outputs. Moving from the large, centralized controllers to smaller distributed ones eliminated thousands of feet of wire, and hours of difficult work installing it. Mike and Brian also wrote the show control software that runs on the central laptop. If everything's working correctly, you can hit one button and sit back and watch the show.

The evening of the show is pure Americana. The baseball field is decorated in American flags and red, white and blue bunting. The show has gained quite a reputation over the years, and people from a wide area arrive early to stake out the best spots. Blankets and picnics are everywhere, and patriotic music plays from the team's sound system. Local civic organizations and scout troops run carnival games and food stands.

Meanwhile, the shoot crew has gathered in the outfield, doing last-minute continuity checks and fixing any problems they find (such as children tripping over the main extension cord). This is also the time for the final safety briefing, handing out fire extinguishers, etc. One of the rules is to have the smallest number of people (all wearing protective equipment) run the show from the forward command area; the rest of the crew spectates from the back of the outfield. As the sun sets, Mike and Brian enter the field to arm their control boxes. The LEDs change from green to red. The field is now no-man's-land.

As darkness settles on the town, the only lights on the field are the softly glowing control boxes, and the laptop screen at the control table. The team makes sure the board is green and that everyone is in position, does a quick countdown, and hits "PLAY." The intro music starts (last year the theme was "At The Movies"), and the show is underway!

Fireworks are an art form like any other, and Joe, Lee and Kyle have gotten quite good at choreographing the style, color and sound of the various Red Rhino products to each year's musical theme. Last year a specially-built array of Roman Candles stood in for the space battle in Star Wars, and sparkling rockets created the twin trails of the DeLorean from Back To The Future (see the video below).

Most shows go off without major problems, but there are occasional glitches. Sometimes the percussive force of one firework going off will dislodge the wiring to an adjacent one (this generally isn't noticeable given the sheer number of fireworks involved). And although the weather at this time of year is typically hot and dry, a rare afternoon thunderstorm before one show moistened the booster charges on the finale shells, causing them to explode much lower than intended. The "low break" certainly looked spectacular, even if it caused the forward team to hastily retreat to the outfield. Importantly, these glitches are valued by the team as opportunities to improve future shows, each of which has been smoother (and more spectacular) than the last.

After the show ends and the crowd expresses their appreciation, the big area lights come on, illuminating the smoking remnants of the team's work. The town's fire department hoses everything down to ensure nothing will go off unexpectedly, and the team moves in to clean up the mess. Exhausted but elated, they'll celebrate the rest of the night at Selden's community center. And the following day, they'll begin planning next year's show.

If you'll be in central Kansas on Sunday, July 1st, the Full-Out Fireworks team invites you to their 12th annual Selden Fireworks Show. If you're unable to attend, you can watch last year's show on Vimeo.

And if you ever decide you want to run your own show, Joe has three suggestions for you: First, always have a fire extinguisher handy. Second, always disarm your system before going into the field. And most importantly, don’t forget to take a moment to step back during the show to enjoy and admire the hundreds of hours of hard work you put into it.

I 👏 Love 👏 This 👏 Post 👏

I am a professional pyrotechnician and when I first read they were amateurs I got really nervous. Lots of people get a hold of our professional stuff and hurt themselves every year... even the professionals get hurt. But I was relieved to see they are keeping it all 1.4g consumer stuff. Good for them! I'd love to go see their show but I'm usually busy that time of the year!

While I somewhat agree with the other comment below that WiFi is sub-optimal for this type of application, it is readily available and likely good enough for their system. I would never use it on a professional show but their show isn't working with our bigger 1.3g shells. Our wireless systems are typically mesh systems with supervisory control and can be pretty pricey. Their home brew system seems to meet their needs and the fact they keep the crew back with safety as a top priority is the most important thing. Props to them!

The specifics of their system isn't covered and I'm curious how their firing system runs cues. Do they download the cue list into the firing modules or does the controller send out a module and channel for each cue? (If anyone from the team reads this feel free to reply back!) The fact they have a master arm on each module is a good sign that they have done their research and understand how their system needs to work to operate safely.

Much respect to the team and I hope they keep putting on a safe show for their community for many years to come!

The idea of using WIFI to trigger explosives makes me very nervous. I've been working with WIFI (as in RF design and embedding in computing products) since the late 90's and want to emphasize that the average hacker/maker should NOT buy an off-the-shelf WIFI board and just put it into a pyrotechnic controller.

For this kind of application, there should be modifications to improve the datalink's reliability and immunity to accidental and deliberate interference, as well as protocols to guarantee that only authorized members of the subnet have access. Fail-safe high reliability coding should be used to guarantee that in case of error the system shuts down and disconnects from power.

The electrical and physical construction should continue this theme with hardware interlocks and the ability to remotely mechanically disconnect from power. As the article says, do your research. Even better, apprentice yourself to someone who has done this professionally for years.

That said, cool article. I wish I lived in a state that allowed this kind of stuff.